The Ruby Object Model - Structure and Semantics 2009-03-03

As part of my compiler project, one of my imminent decisions is what object model to use, and sine I like Ruby it seemed a good time to go through Ruby and look at the guts of the Ruby object model. If you've dabbled in meta-programming etc. for Ruby this post probably doesn't contain much new stuff for you. If you're a beginner you may want to look at a tutorial instead.

If you're somewhere in between, hopefully there may be some insights here and there - especially if you're interested specifically in how things work "under the hood" rather than just what is visible to Ruby.

The information in this post is based largely on the Ruby 1.8.x interpreter (you'll see it referred to as MRI as well - Matz Ruby interpreter - to distinguish it from other Ruby implementations), and we'll look at code fragments, as well as a diagram or two to illustrate.

Suggested reading

The Ruby object model can make you go insane. _why has a great article that illuminates the particular hairy beast that is meta classes

Ruby Objects

Conceptually, Ruby objects consists of the following:

- A reference to the objects immediate class - the MRI interpreter stores this in a field named "klass" and you may see the term "klass" show up in Ruby-land a lot for that reason. For an object that has an meta-class this is a pointer to the meta-class

- A hash table of instance variables

- A set of flags (taint etc.)

MRI "cheats" in that objects of the built-in classes Class, Float, Bignum,Struct, String, Array, Regexp, Hash and File are not real Ruby objects: They don't have the hash table of instance variables. Instead they have a fixed structure. You can still set instance variables for these objects, but behind the scenes MRI 1.8.x at least will then create an instance variable hash table and store that hash table in a hash mapping from the object. This saves a little bit of space if (as is usually the case) most objects of these built in classes don't have instance variables besides the "hardcoded" ones - for small objects like Float in particular this can be a significant saving.

(The following is updated per comment from Rick DeNatale below:)

For some other classes, there's not even a pointer. MRI takes advantage of the fact that there are certain values the object pointer won't take. When MRI determines the class of an "object" it follows the following procedure:

- If the least significant bit (bit 0) is set to 1, the object is a Fixnum. This works since the object pointer will point to an address that's aligned in memory, and so never will have bit 0 set.

- If the value matches 0, it's class is FalseClass, 2 = TrueClass, 4 = NilClass, 6 = undefined.

- If the lowest byte of the value matches 0x0e, it's a Symbol, and the Symbol is determined from the top 3 bytes.

Ruby Classes

There are two types of Ruby classes:- "Real" classes.

- Meta-classes or "eigenclasses" as they are often called. MRI also refers to them as "virtual" classes.

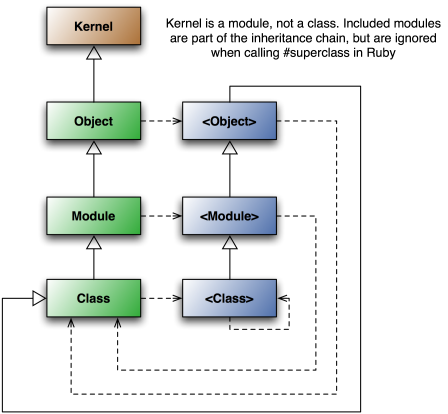

The diagram below shows the actual inheritance of Object, Module and Class in MRI as visible from C. If this doesn't make sense to you, read the section on #send below, but particularly keep in mind that:

- Classes are objects. So they are also instances of another class.

- A class object is NOT an instance of it's superclass. [some class object].class denotes "instance of", [some class object].superclass denotes "inherits from".

- To find out which method implementation is called for any object, you go "out and up". That is, you find the objects "klass", and then follow the "super" chain up until you find a matching method. This gets confusing for classes because they are also objects: You do NOT follow super for the first step for classes - they behave exactly like objects.

So, for example, when sending a message to the object Class, you step out, to the meta class "Class" (in blue), and look for it there, if you don't find it, you follow the solid arrows until you do. This in turn will get you: the Module meta class, the Object meta class, Class, Module, Object, Kernel (since classes in Ruby are open, you might also find someone has reopened the class and caused additional modules etc. to get inserted into the inheritance chain).

Because Ruby's #class method skips metaclasses, you will get "Class" returned if you do Class.class - it's following the same chain as above, but skipping the blue boxes (and any included Module's)

To explore the class/metaclass inheritance in Ruby, you can use this minimal extension to see what values MRI actually operates on:

#include "ruby.h"

VALUE real_super(VALUE self) {

return RCLASS(self)->super;

}

VALUE real_klass(VALUE self) {

return RBASIC(self)->klass;

}

void Init_inheritance() {

rb_define_method(rb_cClass,"real_super",real_super,0);

rb_define_method(rb_cClass,"real_klass",real_klass,0);

}

Put the above in "inheritance.c" and create extconf.rb:

require 'mkmf'

extension_name = 'inheritance'

dir_config(extension_name)

create_makefile(extension_name)

To use it do "ruby extconf.rb ; make", and then:

p Object.real_klass

p Object.real_super

Conceptually a Class object consist of:

- A reference to the objects immediate class (as for a "real" Ruby object) - this would normally be the class "Class"

- A set of flags (taint etc.)

- A hash table of instance variables (for the class)

- A hash table of methods

- A reference to the superclass, i.e. the class this class has inherited from.

Ruby Modules

A Ruby Module is an object that acts as a placeholder for methods and constants. Module is actually the superclass of Class. The main distinction is that you can't create instances of a module, but you can (obviously) create instances of a class.

Internally in MRI the structure of a Module and Class objects is the same.

Taint, Frozen and other flags

MRI defines the following flags for an object:

- Singleton

- Mark

- Finalize

- Taint

- Exivar

- Freeze

- A number of "user" flags.

"Singleton" is set on objects of type Class that are meta-classes.

Mark and Finalize are used by the garbage collector. "Taint" is used for the "taint mode" - depending on the security level, some objects may be marked as "tainted" and thus unsafe, and certain operations may be disallowed.

"Exivar" is used for objects of the "fake" builtin classes to indicate that this instance has an external instance variable hash table that must be looked up elsewhere.

"Freeze" prevents an object from being modified.

Of these, only Singleton, Taint and Freeze represent behavior that are "observable" from inside Ruby, as opposed to when delving under the hood of MRI.

Send

Send is perhaps the most vital concept in the Ruby object model beyond classes and objects. Almost all actions in Ruby at least conceptually boils down to sending a message to an object.Send operates roughly like this (lots of details omitted):

- Identify the class to start at. "Objects" of class Fixnum are treated specially since they're not actually objects at all. nil, true and false are also special cased. For other objects this means grabbing the "klass" pointer.

- The method cache is checked, to avoid complex lookups of the method on repeated calls.

- If not in the method cache, the method is searched for. This is done by lookup up the method in the "klass", and if not found replace "klass" with "klass->super" and try again, until the top of the inheritance chain is found (in which case the method doesn't exist). The result is put in the cache.

- If the method is not found, method_missing is called in roughly the same way.

- private/protected access checks are carried out

- Access checks are done in case the safe level is set to trigger exceptions for unsafe operations.

- The arguments are prepared

- A "stack frame" is prepared - MRI maintains it's own "Ruby stack"

- If the method is a C function various special setup is done.

- If the method is an attribute getter/setter (attr_accessor/attr_read/attr_write), the appropriate built in MRI functions are called rather than executing a method body. Same with methods consisting of "super"

- The method is finally called.

This makes MRI method calls extremely expensive. The method cache alleviates some of it, but the remaining work still has a huge cost compared to C++ for example, where the worst case runtime overhead is a virtual method in a multiple-inherited class, which consists of an indirect pointer lookup and a call to a "thunk" function that fixes up the object pointer (a couple of instructions at most) so the method can access the right data, and jumps to the real method, and the typical cost is an indirect pointer lookup and a call instruction. Some of this overhead is avoidable in a more streamlined implementation, but quite a bit of it is extremely hard or impossible to get rid of within the required semantics of Ruby.

method_missing

In MRI, relying on method_missing is even more expensive than #send, as the method first needs to be looked up and then method_missing itself causes another looup, but the method cache makes it a reasonable choice for dynamically "adding" methods to objects as "send" is short-circuited early in loops etc., so after the first call the cost is fairly low. A brief benchmarks surprisingly shows that defining a new method using #define_method is actually slower than relying on method_missing. Here's the benchmark:

#!/bin/env ruby

require 'benchmark'

class Foo

def test1

end

def method_missing sym

if sym == :test2

end

end

end

Foo.class_eval do

define_method :test3 do

end

end

n = 1000000

f = Foo.new

Benchmark.bmbm(20) do |x|

x.report("test1") { n.times { f.test1 } }

x.report("test2 (method_missing)") { n.times { f.test2 } }

x.report("test3 (define method)") { n.times { f.test3 } }

end

And here are the results from one of my machines:

$ ruby send_vs_method_missing.rb

Rehearsal ----------------------------------------------------------

test1 1.390000 0.390000 1.780000 ( 1.788041)

test2 (method_missing) 1.660000 0.460000 2.120000 ( 2.626747)

test3 (define method) 1.880000 0.450000 2.330000 ( 2.326830)

------------------------------------------------- total: 6.230000sec

user system total real

test1 1.320000 0.450000 1.770000 ( 1.777432)

test2 (method_missing) 1.660000 0.480000 2.140000 ( 2.124609)

test3 (define method) 1.870000 0.450000 2.320000 ( 2.326343)